Originally a Welsh cheese from just north of Cardiff, Caerphilly’s West Country history has been intimately interwoven with that of Somerset’s most famous son, Cheddar, since at least the C19th. Typically quicker to mature, smaller and lighter in weight, the cheeses were produced to use up excess milk on the farm and as a more immediate ‘cash cow’ whilst the pampered Cheddars lay sleeping in the local caves/cheese sheds. But Caerphilly soon became a popular local cheese in its own right, surviving industrialisation and both world wars with their attendant loss of labour and the Ministry of Food’s notorious ‘National Cheese’ mandate.

By the 1950s, however, only one producer remained: Duckett’s Farm in Wedmore on the Somerset Levels. Before they too ceased production, they passed on the baton to nearby Westcombe Dairy were it continues to be made today appropriately alongside a rather famous Cheddar. The Duckett Family also bequeathed their cheesemaking skills to the Trethowans who initially started making Gorwydd Caerphilly in Wales, later bringing things full circle by moving production to North Somerset. Despite its roots and name therefore, Caerphilly is as much the product of Somerset’s rolling hills as it is of Welsh valleys. Sir John Squire, writing in 1937 in his wonderful Cheddar Gorge – a Book of English Cheese recounts the ‘sorry little story’ of his disastrous trip to the town of Caerphilly and his near inability to procure any of the famous cheese in its original homeland. So, arguably, Somerset has rather more claim on this noble cheese than the uplands of Glamorgan …

Westcombe’s raw cow’s milk take on matters comes clad in a beautiful natural rind of mottled browns with some black, white and yellow detailing reminiscent of the local ochre soils. Immediately beneath is a thin layer of slightly translucent caramel-coloured paste with a soft fudgy texture and delightful mushroom, allium flavours. The majority of the cheese is, however, a pure ivory with textures that range from smooth silk to slightly chewy chalk as you move through the curdy paste. Flavours are likewise a lovely journey from clean lactic tang to savoury-mineral and back. Matured for a relatively restrained 6-9 weeks, it is nonetheless complex, lilting and really very lovely indeed. It's a cheese with a past and, I very much hope, a future.

Ricotta is synonymous with the bland milky bulk used in cooking throughout Italy and beyond: ravioli/cannelloni fillings, cheesecakes, gnocchi, pancakes … the list goes on. It’s a whey cheese made from the left-overs of cheese production, sheep’s milk cheeses like Pecorino but also cow, goat and even buffalo milk products. It comes down to the different proteins in the milk: Casein (the much-prized cheese-making stuff) goes off to make the wonderful array of cheeseboard beauties – Parmigiano Reggiano, say, or Provolone and Mozzarella di Bufala (in the case of buffalo milk); the remaining whey contains different protein structures (notably members of the albumin and globulin families) which can then be re-used (re-cooked, in fact, hence the name ‘ricotta’) to make a sweet, fresh cheese or cheese-like confection.

And that’s the end of the story for the majority of ricotta, scooped up and popped into its familiar conical tubs and destined for the kitchens of the world.

But some is destined for greater things. Ricotta Salata (literally ‘Salted Ricotta’) is further pressed and salted to remove moisture and left to dry and mature. The resulting semi-hard cheese is considerably firmer than the basic stuff, with an intense salty hum and a nice balance between its sweet heritage and umami upbringing. Too salty for the table, its closer texture means that it can be grated and used in place of Parmesan or Pecorino on top of pasta dishes. It’s an essential component of Sicily’s pasta alla norma, for example, where its saline chalkiness offsets the sweet aubergine and acidic tomatoes wonderfully. And Rachel Rody – of A Kitchen in Rome fame – simply grates it over a salad of tomatoes and raw onion. Anointed with good olive oil, it’s a simple and delightful dish which of course relies on the excellence of the toms most of all. I think of Ricotta Salata more like a seasoning than a cheese per se and this dish shows it off particularly well.

An ancient cheese, one that feels as though it might have come straight from the back of the Cyclopes’ caves. And today Greece still makes cousins of Ricotta from goat and/or sheep’s milk, cheeses like Mizithra/Myzithra and Manouri (the latter a by-product of the vast Feta industry). Inevitably, they are rather good snuck into a moussaka or two.

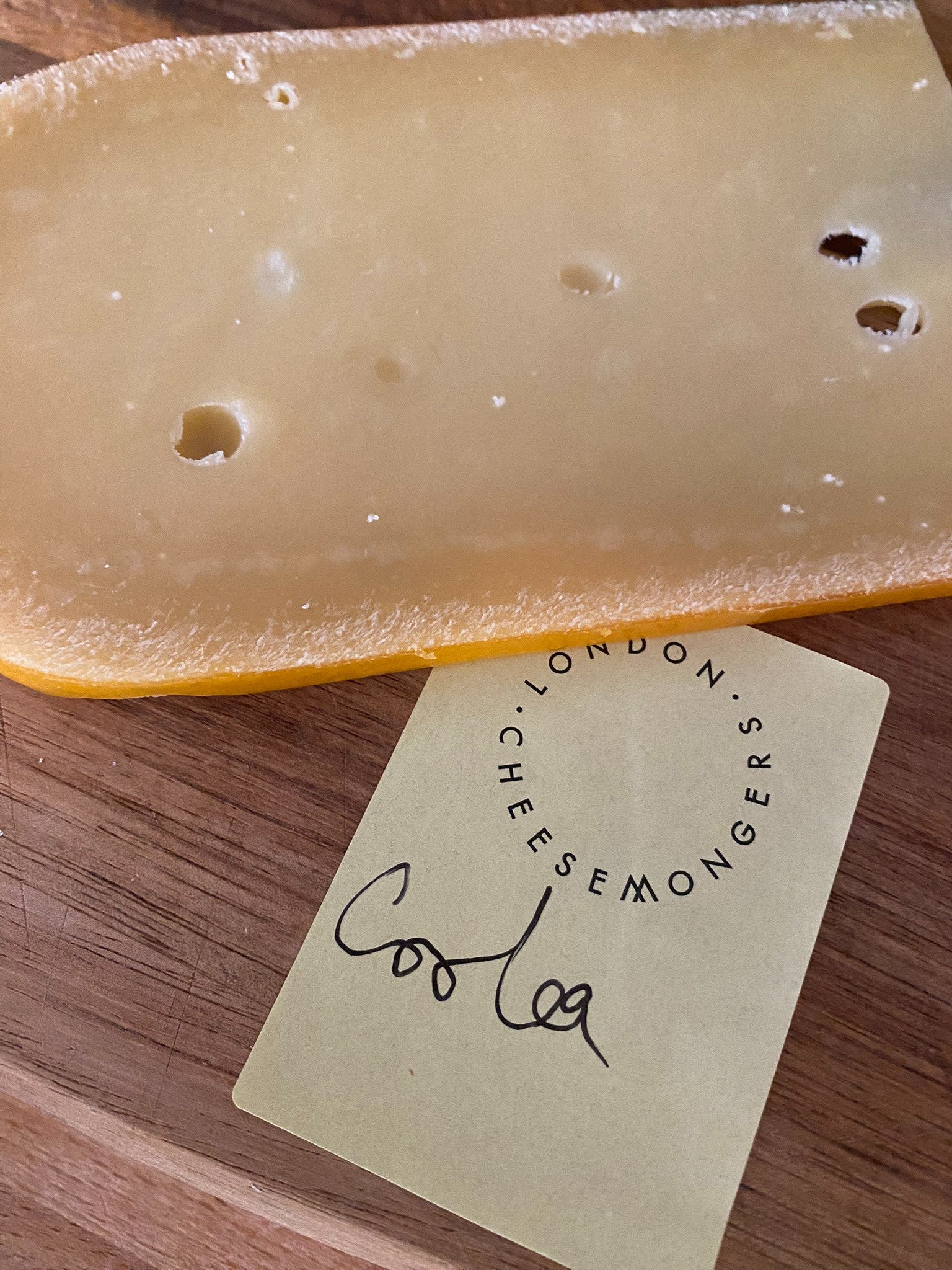

Coolea is the product of a Dutch family relocating to southern Ireland and devising a new cheese with the local milk to a recipe not a million miles from their homeland’s traditional Gouda. And yes, it’s as good as that sounds. The couple in question, the Willems, set up shop in the 1970s on a farm in the mountains of Coolea, County Cork. Using pasteurised full-cream cow’s milk, they set about making their wonderful hand-crafted cheese – a truly artisan product that has since gone on to win multiple awards.

The cheese can now be found in a number of forms including mature (min. 12 months'ageing) and extra-mature (up to two years). As it develops, it takes on an utterly delicious, fudgy sweetness that marries perfectly with the salty umami of its semi-hard texture. If you’re a fan of Oud Gouda then this cheese will certainly appeal, but it’s sweeter than its continental cousin, less unremittingly savoury. I suspect that this is a reflection of the superlative quality of south-west Ireland’s milk. And of the skill with which it's handled in the dairy and during the cheese-making process.

It’s almost heresy to say it, but I think this is a case of the modern upstart outstripping its original model. And, as a card-carrying Gouda fancier, I don’t say that lightly. It would certainly have a place on my Irish cheese board (alongside Cork’s washed-rind Gubbeen and Northern Ireland’s Young Buck, perhaps). But it can more than hold its own internationally and wouldn’t be out of place beside a Roquefort or a Brie de Meaux. And that’s praise indeed.

Supermarket Red Leicester is a pretty dismal affair: rubbery, luridly coloured and often lacking any kind of real cheese texture. Basic, sweaty putty. But when you happen upon the wonderful Sparkenhoe, you suddenly realise why anyone would want to eat or indeed make the stuff. Artisan Red Leicester had died out until it was revived by the Leicestershire Handmade Cheese Co. about 20 years ago. Drawing on the historical record and memory of the wonderful cheese that used to be made in the area local dairy farmers, the Clarkes, took milk from their herd of Holsteins, added the cheese’s traditional colouring agent, Annatto (derived from seeds of Central/South America’s achiote tree) and started making the traditional British territorial again.

Theirs is an unpasteurised, traditionally made, cloth-bound cheese, almost unrecognisable to those weaned on the red rubber version. Younger Sparkenhoe (usually around 6 month old) has a lovely nutty, almost caramel-like sweetness and an interesting texture somewhere between crumbly and chewy.

There’s a vintage version, too, that really dials up the umami hum and revels in its slightly drier, almost crunchy texture. You can find it in quality cheese mongers where it can be matured for 12-14 months. The Clarke’s have gone on to add two blue cheeses (Sparkenhoe and a Shropshire) as well as the mould-ripened Bosworth Field to their stable – all made with the farm’s raw milk.

Red Leicester is part of this country’s cheese heritage and it’s wonderful to have a quality version available once more. Its beautiful ruddy looks are great on a cheeseboard and it works well in cooking, too. The fine folk at the Courtyard Dairy (who, incidentally, stock the vintage version) have a recipe for chef Mark Byron’s Twice Baked Sparkenhoe Soufflé. It’s a yes from me.

Get to know more about cheese with my full-length articles: